Mirar hacia arriba, luego mirar hacia abajo y volver a mirar hacia arriba otra vez Mar Ramón Soriano From February 23 to May 3 A Coruña

Dry in the sun, if any.

Placing damp bowls on the drying.

Putting on the enamel. Putting on the enamel, on the inside only. They are cooked. They march in the baskets.

R. Matilda.

Sometimes it is interesting to look at yourself from the perspective of one who has looked at you before. At other times it is interesting to look at something you have never seen but which is somehow familiar. There is a gaze that exoticizes the external and also one that turns one's own into a sign through its repeated self-representation. The dynamics of power are intertwined between the observer and the observed, also between territories and, in the same way, they can be exercised spatially from the systems of placement.

This exhibition is based on two journeys that are, in reality, the same. Mine, from Galicia to New York and back to Galicia, and Ruth Matilda Anderson's, the same but in the opposite direction. The relationship between them allows me to work with images and meanings of both territories that are used and analyzed through different layers of observation and interpretation.

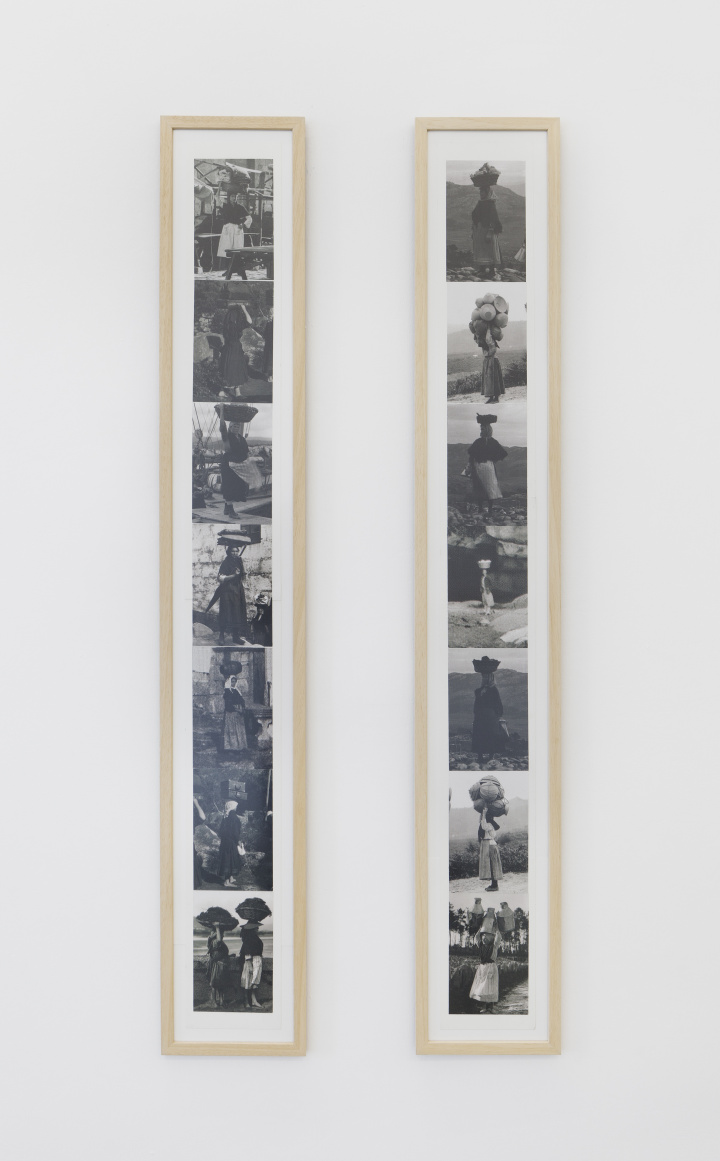

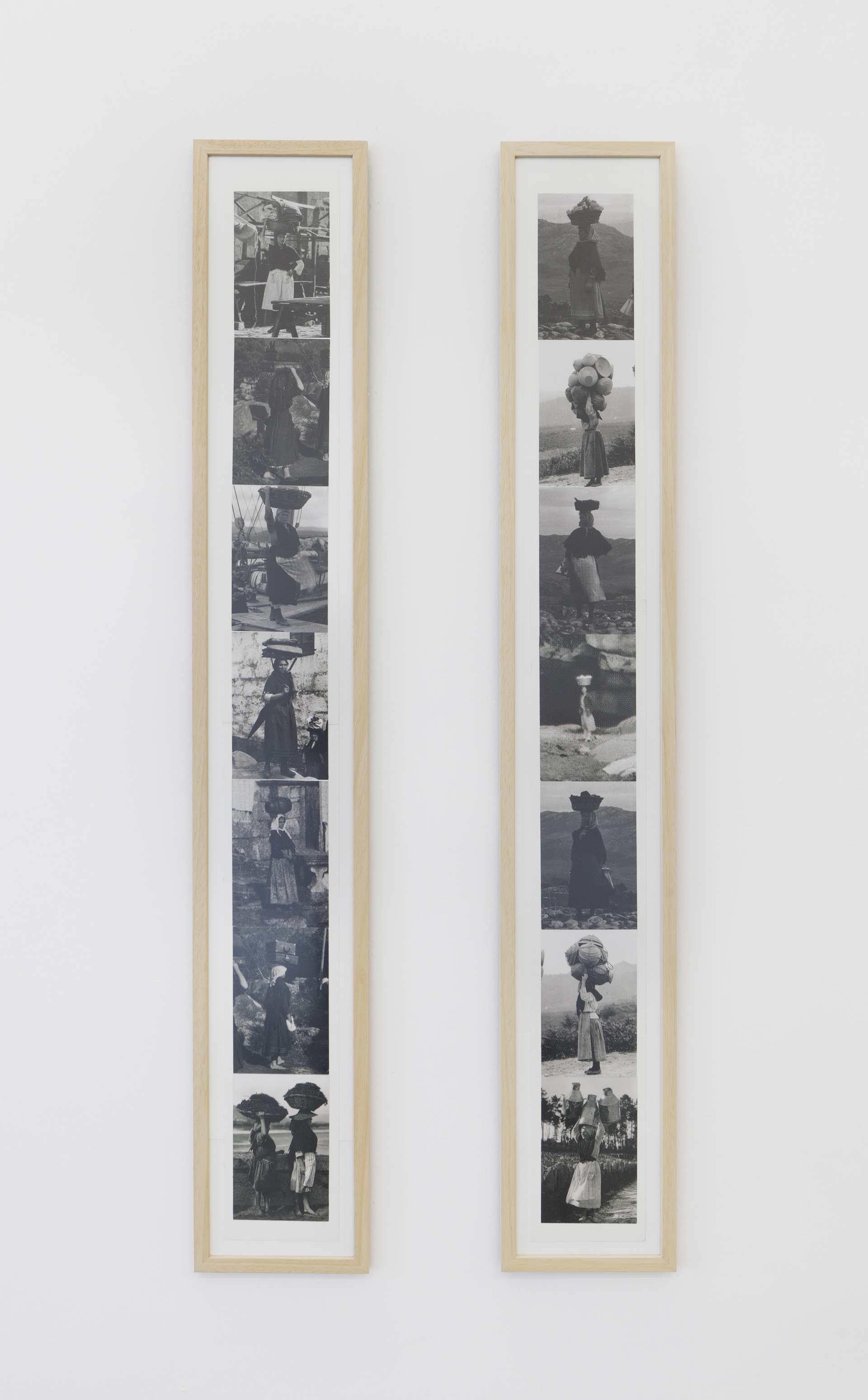

In the images captured by this American in Galicia in the twenties of the last century, we observe garments and shirts, both dressed and hung to dry. We also contemplate jewelry and ornaments, elements used for photography, and costumes that are not dressed, but extracted from closets and chests for their immortalization. This work, necessary at the patrimonial level, can be misleading if we consider the photographic image as proof of veracity. Similarly, I observe the new city from my scrutinizing but also touristic perspective of the one who looks and is surprised by what is already known. The familiar having seen this place in numerous films and also by visiting this photographic archive of our past.

On the other hand, the estrangement of Galicia that emanates from these images is also produced from the gaze of the person who lives there, observing a different past and transformed cities. My estrangement also moves towards the new: the size of the buildings, the school buses or the American cheerleaders, which end up interesting me both in terms of structure and for being a popularly feminine activity and, moreover, somewhat reviled. These experts in spatial constructions and three-dimensional sororities remind me of Niñodaguia's apañadeiras, carrying huge baskets of pots and pans on their heads. The exercises and formations of cheerleaders and the stacking and loading systems follow basic physical rules of arrangement and loading that can be transferred to the sculptural language. Verticality is presented as a constant in this signification of powers, from skyscrapers to the human impetus to rise to obtain a privileged position, to observe from above and be closer to the sky.

In Looking up, then looking down and looking up again I work with what is above us and what is below us, the powerful and the humble. Feet and socks, bodies and ornaments, roofs, loads, antennae and pom-poms. Their pleated skirts and our shirts are confused with roofs and pockets. The peaks here and there are mixed with bare feet and also with socks, representing that which is closer to the ground. What is above and what is below signify and in the works presented are transmuted. What is pointed is now a glass, container or bowl and what is lower, near the earth that serves as the foundation of the body, is elevated. The tiles function as bowls, the skirts cover nothing. The costume jewelry functions as low-budget ornamentation, as pose and as representation. This alludes somehow to photographic posing, putting on Sunday, Sunday shoes. There are layers and layers and layers and filters and transparent filters projected on the images by the photographer and also by the recipients of the photograph. This superimposition of transparencies interests me as a glaze and filter.

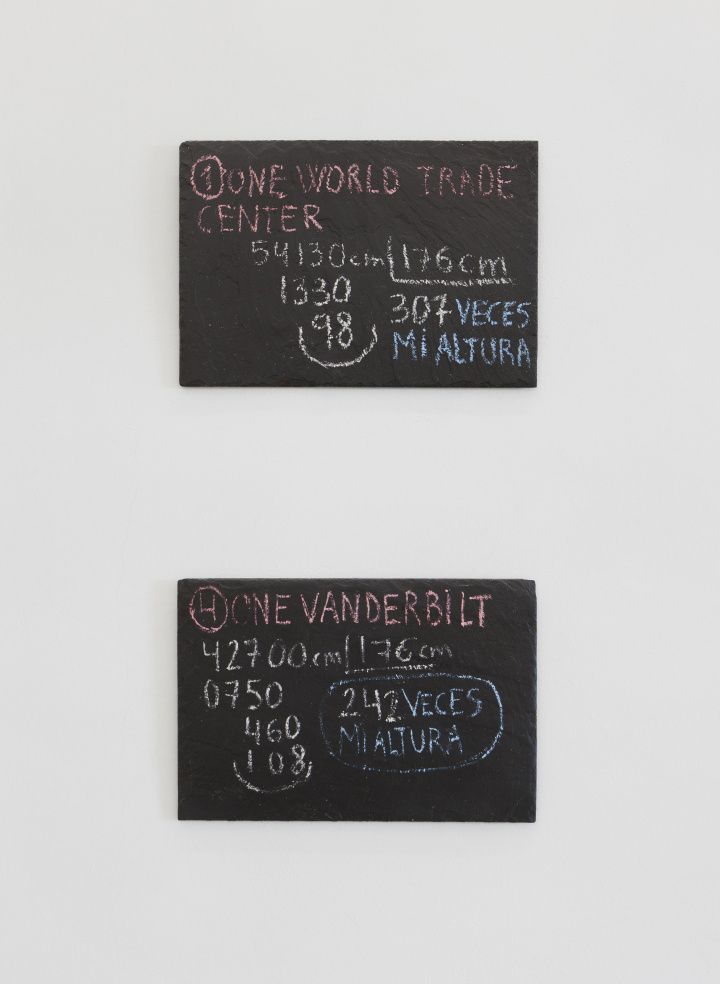

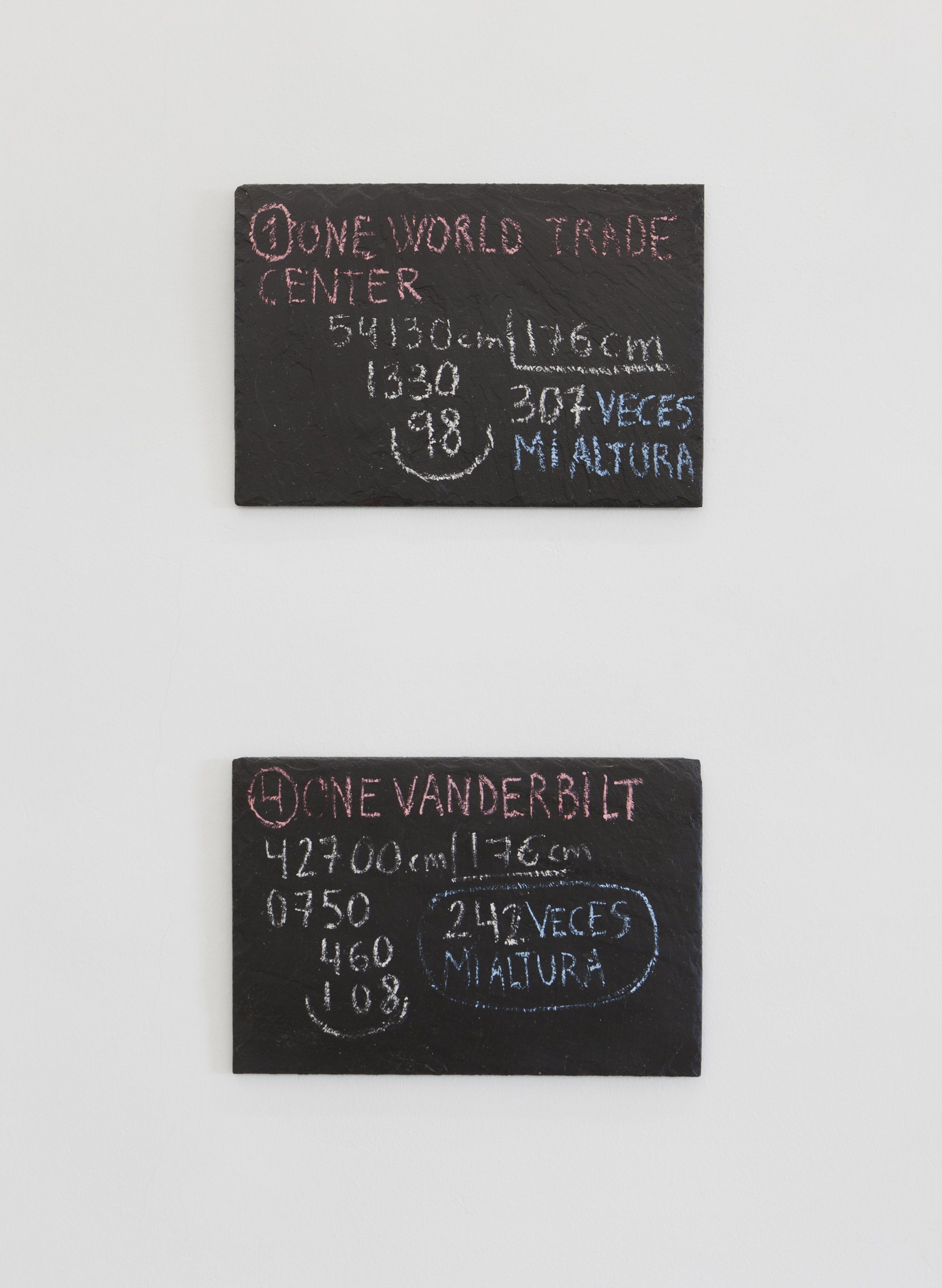

Niñodaguia's own forms are revised and transformed, in Oito femias deitadas and Oito machos recipientes, based on traditional pottery forms of this context, volumes that were placed on top of the houses to crown them. Being the femias rounded, the males are spikes pointing to the sky. The simple exercise of turning them upside down annuls their sharp aggressiveness, turning them into a vase, a vase and a vessel. Both works function as horizontal lines in space that coexist with other vertical works. In The parts where I have to fold a skyscraper, slate tiles are used to calculate with chalk the relationship between my height and that of the tallest buildings in New York. In Apañadeiras apañandose unhas ás outras (I'll be there for you, When the rain starts to pour) I build towers out of these women who, in addition to holding their loads, hold themselves up and look at each other. In the four works titled The skirts, in reality, can be the roofs of something, the spatial placements of pompoms, skirts, feet and socks are inverted. The ceramic antennas serve to raise the structures a few centimeters higher, the constructions are buildings and also human figures. The works on paper distributed around the room are exercises in transparencies, superimpositions, folds and pockets. Here we bring together what is shown and what is hidden. What is found and what is kept. They are both garment and garment.

Mar Ramón Soriano

Structures

Columns

Towers

Scraper

Triangles

Count

Add

Fold

Sky

Floors

Feet

Top

Sticks

Pins

Legs

Walls

Foundations

Bodies

Support

Uptown

Downtown

Express

Local

Upload

Grow up

Crossing the river from Brooklyn to Manhattan

We all wonder how to start a journey, learn, decide to return, and finally return. With an ocean in between, a body of water that connects both countries, Ruth Matilda Anderson's journey was to some extent an experiment, like Mar Ramón's, in a new city, where the first thoughts about this work were conceived.

Researching in Ruth Matilda Anderson's archive in New York teleports at a certain point to our origins, where we can encounter the known in completely unknown terrain. A paradox that an artist discovers crossing from Brooklyn to Manhattan, from a temporary physical home, to a recognizable home, in photographs, letters, records. Getting on a subway in New York uptown or downtown means choosing a totally different path, yet using the same line of transportation. A journey that goes in both directions can be repeated. Mar plays with transparencies as a deception in the archives, the pockets that hide secret information, the nooks and corners to keep treasures.

The surprise before codes and mechanisms that are known in a huge city today can be transferred, to a look that goes back and forth, folds and folds back, starting at the beginning of the century of an American in Galicia.

Influenced by one of the oldest crafts in the world, pottery, the work is composed of pieces that have a complementary combination of support and absence, a similarity like the one that the cacharreiros of Niñodaguia require with the help of the apañadeira balancers. In order to elaborate pottery objects and advance culturally as a society, the balance of these women was essential. And it is in the artist's language, where the silhouette of apañadeiras at work can resemble that of a cheerleader at work. The North American figure of cheerleader literally says that she leads the cheer. To the team, to the achievement, to the triumph. And they celebrate victory.

During her production to date, Mar has worked with clay, fabrics, cottons, tissues, sacks and metaphors. Tensions of wall objects, which also represent human tensions, between the opulent and the simple, and the various utilities of an object, such as the tiles that make up a roof, the foundations of a house, the value of the entrance on a piece of paper to a space or the number on a bill. Looking up, then looking down and looking up again makes one think of a piece of popular pottery, mixed with the symbol of a pompom, the human stature and its correspondence to a skyscraper.

Elena Pérez-Ardá López

February 2024, Brooklyn, New York